Book of Deuteronomy

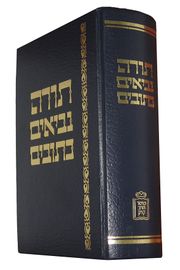

Deuteronomy (Greek: Δευτερονόμιον, "second law") or Devarim (Hebrew: דְּבָרִים, literally "things" or "words") is the fifth book of the Hebrew Bible, and the fifth of five books of the Jewish Torah/Pentateuch.

A large part of the book consists of five sermons delivered by Moses reviewing the previous forty years of wandering in the wilderness, and the future entering into the Promised Land. Its central element is a detailed law-code by which the Israelites are to live within the Promised Land.

Theologically the book constitutes the renewing of the covenant between YHWH, the Jewish God, and the "Children of Israel".

One of its most significant verses is considered to be Deuteronomy 6:4, which constitutes the Shema, a definitive statement of Jewish identity: "Hear, O Israel: the LORD (YHWH) (is) our God, the LORD is one."

Traditionally seen as recording the words of God given to Moses,[1] modern scholarship dates the book to the late 7th century BC, a product of the religious reforms carried out under king Josiah, with later additions from the period after the fall of Judah to the Babylonian empire in 586 BC.[2]

Contents |

Title

The English title is derived from the Greek Deuteronomion (Δευτερονόμιον, "second law") and Latin Deuteronomium, which in turn is derived from the erroneous Septuagint rendering of the Hebrew phrase "mishneh ha-torah ha-zot" - "a copy of this law", in Deuteronomy 17:18, as "to deuteronomion touto" - "this second law". In Hebrew the book is called Devarim (דְּבָרִים, "words", specifically spoken words),[3] from the opening phrase Eleh ha-devarim, "These are the words..."

Summary

|

Part of a series

of articles on the |

|---|

| Tanakh (Books common to all Christian and Judaic canons) |

| Genesis · Exodus · Leviticus · Numbers · Deuteronomy · Joshua · Judges · Ruth · 1–2 Samuel · 1–2 Kings · 1–2 Chronicles · Ezra (Esdras) · Nehemiah · Esther · Job · Psalms · Proverbs · Ecclesiastes · Song of Songs · Isaiah · Jeremiah · Lamentations · Ezekiel · Daniel · Minor prophets |

| Deuterocanon |

| Tobit · Judith · 1 Maccabees · 2 Maccabees · Wisdom (of Solomon) · Sirach · Baruch · Letter of Jeremiah · Additions to Daniel · Additions to Esther |

| Greek and Slavonic Orthodox canon |

| 1 Esdras · 3 Maccabees · Prayer of Manasseh · Psalm 151 |

| Georgian Orthodox canon |

| 4 Maccabees · 2 Esdras |

| Ethiopian Orthodox "narrow" canon |

| Apocalypse of Ezra · Jubilees · Enoch · 1–3 Meqabyan · 4 Baruch |

| Syriac Peshitta |

| Psalms 152–155 · 2 Baruch · Letter of Baruch |

|

|

Deuteronomy consists of 34 chapters and is in the form of a series of sermons delivered by Moses to the Israelites in the plains of Moab before their entry into the Promised Land.

Significant chapters

Chapters 5-6

Deuteronomy 5 opens with Moses emphasizing the authority of YHWH and linking the Decalogue with Sinai Covenant. The Decalogue, which precedes the more detailed stipulations of later chapters sets a theological foundation for the rest of the law. Within the first few verses of chapter six is the famous shema, "Hear, O Israel, YHWH (is) our God, YHWH is one." (6:4-9 NRSV) The exhortation surrounding the shema and linking chapters 5 and 6 focuses on practically remembering and weaving the law into everyday life. The Law is both grounded in history and conditional, although YHWH's overarching promise is unconditional.[4]

Chapter 7

Deuteronomy 7 is notable because it contains language that, without the modifications found in the Talmud (Oral Law), seems to be an overt instance of YHWH ordering the Israelites to carry out ethnic cleansing against nonbelievers resident in the land that the latter will be occupying under the former's sponsorship.

When the LORD your God brings you into the land you are entering to possess and drives out before you many nations -- the Hittites, Girgashites, Amorites, Canaanites, Perizzites, Hivites and Jebusites, seven nations larger and stronger than you -- 2 and when the LORD your God has delivered them over to you and you have defeated them, then you must destroy them totally. Make no treaty with them, and show them no mercy. 3 Do not intermarry with them. Do not give your daughters to their sons or take their daughters for your sons, 4 for they will turn your sons away from following me to serve other gods, and the LORD's anger will burn against you and will quickly destroy you. 5 This is what you are to do to them: Break down their altars, smash their sacred stones, cut down their Asherah poles and burn their idols in the fire. (Deut 7.1-5)

Although it has been alleged that this passage promotes and condones genocide, it should be noted that the actions listed do not include physical violence against nonbelievers as opposed to their idols, but simply restriction of residency to the worshippers of YHWH. The application of Biblical hermeneutics would therefore prohibit anything more than forced emigration of residents unwilling to abandon worship of any other gods.

Chapter 8

The central theme of Deuteronomy 8 is an exhortation to Israel to not forget YHWH when they have taken possession of the 'promised land.' Craigie comments on the frequency of remembering and forgetting language in the chapter.[5] In the opening verses Moses reminds the Israelites of YHWH's miraculous provision during their years wandering in the Wilderness. Then in the midst of an extravagant description of the promised land, there is the reminder to not forget YHWH during times of prosperity. As Brueggemann observes "Israel does not have many resources with which to resist temptation. Their chief one is memory. At the boundary [of the 'promised land'] Israel is urged to remember."[6]

Chapter 12

Deuteronomy 12 is focused on the correct worship of YHWH. It opens with instructions to destroy Canaanite religious places. The purpose here being to keep Israel religiously pure and ideologically distinctive. The chapter then moves to the cultic aspect of worship; the type and manner of sacrifice. Significantly there is a reference to "the place that the Lord your God will choose" (Deuteronomy 12:5) for the centralised worship of YHWH.[7]

Chapters 16-18

Along with law and history, the book of Deuteronomy contains instructions about various festivals including the Passover and Unleavened Bread festival. Craigie says that the "Passover was a celebration and commemoration of the event on which the covenant community of God was established."[8] Deuteronomy 16 also then reviews the Feast of Weeks, later known to Christians as Pentecost and the Feast of Tabernacles or Booths. The second half of chapter 16 and all of chapter 17 through to chapter 18 is focused on the provision of justice and the offices of Kings, priests and prophets. The distinctive feature of this early Hebrew justice system is the right of appeal and the finality of judgement to prevent payback.[7] The office of King is a heavily regulated one unlike the generous provisions for Levites at the beginning of chapter 18. After a warning against foreign religious practices the role of prophet is delineated as one who mediates between YHWH and Israel.[7]

First sermon

Deuteronomy 1-4 recapitulates Israel's disobedient refusal to enter the Promised Land and the resulting forty years of wandering in the wilderness. The disobedience of Israel is contrasted with the justice of God, who is judge to Israel, punishing them in the wilderness and destroying utterly the generation who disobeyed God's commandment. God's wrath is also shown to the surrounding nations, such as King Sihon of Heshbon, whose people were utterly destroyed. In light of God's justice, Moses urges obedience to divine ordinances and warns the Israelites against the danger of forsaking the God of their ancestors.

Second sermon

Deuteronomy 5-26 is composed of two distinct addresses. The first, in chapters 5-11, forms a second introduction, expanding on the Ethical Decalogue given at Mount Sinai. The second, in chapters 12-26, is the Deuteronomic Code, a series of mitzvot (commands), forming extensive laws, admonitions, and injunctions to the Israelites regarding how they ought to conduct themselves in Canaan, the land promised by the God of Israel. The laws include (listed here in no particular order):

- The worship of God must remain pure, uninfluenced by neighbouring cultures and their idolatrous religious practices. The death penalty is prescribed for conversion from Yahwism and for proselytisation.

- The death penalty is also prescribed for males who are guilty of any of the following: disobeying their parents, profligacy, and drunkenness.

- Certain Dietary principles are enjoined.

- The law of rape prescribes various conditions and penalties, depending on whether the girl is engaged to be married or not, and whether the rape occurs in town or in the country. (Deuteronomy 22)

- A Tithe for the Levites and charity for the poor.

- A regular Jubilee Year during which all debts are cancelled.

- Slavery can last no more than 6 years if the individual purchased is "thy brother, an Hebrew man, or an Hebrew woman."

- Yahwistic religious festivals—including Passover, Shavuot, and Sukkot—are to be part of Israel's worship

- The offices of Judge, King, Kohen (temple priest), and Prophet are instituted

- A ban against worshipping Asherah next to altars dedicated to YHWH, and the erection of sacred stones

- A ban against children either being immolated or passing through fire (the text is ambiguous as to which is meant), divination, sorcery, witchcraft, spellcasting, and necromancy

- A ban preventing blemished animals from becoming sacrifices at the Temple

- Naming of three cities of refuge where those accused of manslaughter may flee from the avenger of blood.

- Exemptions from military service for the newly betrothed, newly married, owners of new houses, planters of new vineyards, and anyone afraid of fighting.

- The peace terms to be offered to non-Israelites before battle - the terms being that they are to become slaves

- The Amalekites to be utterly destroyed

- An order for parents to take a stubborn and rebellious son before the town elders to be stoned.

- A ban on the destruction of fruit trees, the mothers of newly born birds, and beasts of burden which have fallen over, or are lost

- Rules which regulate marriage, and Levirate Marriage, and allow divorce.

- The procedure to be followed if a man suspects that his new wife is not a virgin: if the wife's parents are able to prove that she was indeed a virgin then the man is fined; otherwise the wife is stoned to death..[9]

- Purity laws which prohibit the mixing of fabrics, of crops, and of beasts of burden under the same yoke.

- The use of Tzitzit (tassels on garments)

- Prohibition against people from Ammon, Moab, or who are of illegitimate birth, and their descendants for ten generations, from entering the assembly; the same restriction upon those who are castrated (but not their descendants)

- Regulations for ritual cleanliness, general hygiene, and the treatment of Tzaraath

- A ban on religious prostitution

- Regulations for slavery, servitude, vows, debt, usury, and permissible objects for securing loans

- Prohibition against wives making a groin attack on their husband's adversary.

- Regulations on the taking of wives from among beautiful female captives.[10]

- A ban on transvestism.[11]

- Regulations on military camps, including a cleanliness regime for soldiers who have had wet dreams and procedures for the burial of human excrement.[12]

Third sermon

The concluding discourse sets out sanctions against breaking the law, blessings to the obedient, and curses on the rebellious. The Israelites are solemnly adjured to adhere faithfully to the covenant, and so secure for themselves, and for their posterity, the promised blessings.

Death of Moses

Moses renews the covenant between God and the Israelites, which is conditional upon the people remaining loyal to YHWH. By the direction of YHWH, Moses then appoints Joshua as his heir to lead the people into Canaan. He writes down the law and gives it to the Priests, commanding them to read it before all Israel at the end of every seven years, during the Feast of Booths.

Three short appendices follow:

- The Song of Moses, which Moses wrote and taught the people at the request of God (Deuteronomy 32);

- The Blessing of Moses, which Moses laid upon the individual tribes of Israel (Deuteronomy 33);

- The death of Moses (Deuteronomy 34).

Composition and Structure

Composition

Views about the composition and date of the Book of Deuteronomy can be divided into four major groups:[13]

- Deuteronomy was primarily the work of Moses: This was the traditional view until the beginning of the nineteenth century. Scholars holding this view have argued that the New Testament authors attested to Mosaic authorship and that although kingship is mentioned, Jerusalem is omitted and the book presents itself as being written prior to the first millennium. Meredith G. Kline more recently proposed Deuteronomy should be viewed as a suzerain/vassal treaty between God and the people of Israel mirroring other ancient near Eastern treaties from the second millennium.[14] There are scholars who hold this view such as Meredith G. Kline and Christopher Wright[15] who concede that some additional post-Mosaic material and editing has occurred.[16]

- Deuteronomy was the work of Moses, but it was compiled and substantially edited during King Josiah's reforms: Theodor Oestreicher suggested in 1923 that Josiah began reforms prior to the discovery of the law and the discovery of 'the book' only added impetus to the reform.[17] Scholars holding this view such as E. Robertson hold that a core Deuteronomistic amount of material is Mosaic but that subsequent additions were made around the time of King Saul.[18] Gerhard Von Rad took this view in 1938, suggesting that the original Mosaic material was edited by Levities from the Northern Kingdom, which subsequently became the book of law discovered by King Josiah.[19]

- Deuteronomy was the work entirely of King Josiah and his reforms: M. L. de Wette initiated this view in 1805 by suggesting King Josiah had Deuteronomy created as a type of "pious fraud" to further his agenda of religious reform.[19] Since then this has become the dominant view among most scholars.[20] Proponents of this view point to the lack of penalties for attending feasts and theological theme of centralized worship.[21]

- Deuteronomy was the work of the Jews in Babylonian exile: Martin Noth in 1943 published a thesis that suggested Deuteronomy through Kings was a single Deuteronomistic history, largely the product of one author.[22] Noth held that Deuteronomy was competed during the exilic period.[22]

Structure

Deuteronomy, unlike the Book of Numbers, is largely a book of speeches that both look back on the history of the Israelites wanderings in the wilderness and look forward to them entering 'promised land.'[23]

|

Wright:[24]

|

Troxel:[25]

|

Thompson:[26]

|

Wenham:[27]

|

Themes

Covenant

The Covenant, a major theme of the Pentateuch, plays a central role in the theology of Deuteronomy.[28] Israel is YHWH's vassal, and Israel's tenancy of the land is conditional on keeping the covenant, which in turn necessitates tempered rule by state and village leaders who keep the covenant. "These beliefs," says Norman Gottwald, "dubbed biblical Yahwism, are widely recognized in biblical scholarship as enshrined in Deuteronomy and the Deuteronomistic History (Joshua through Kings), with pronounced affinities to the Pentateuchal 'E' source and to the prophets Hosea, Jeremiah, and Malachi."[29]

Israel

Dillard and Longman stress in their Introduction to the Old Testament the 'living' nature of the covenant between YHWH and Israel as a nation.[30] The people of Israel are addressed by Moses as a unity. Their allegiance to the covenant is not one of obeisance, but comes out of a pre-existing relationship between YHWH and Israel, established with Abraham and attested to by the Exodus event. In many ways the laws of Deuteronomy set the nation of Israel apart, signally the unique election of the Jewish nation.

Land

The book of Deuteronomy is set immediately prior to the Israelite invasion of the 'promised land.' Therefore it is not surprising that land forms a major theme of the book. Israel is called to possess the land and many of the laws, festivals and instructions in Deuteronomy are given in the light of Israel's occupation of the land. Deuteronomy presents God as giving Israel the land. Dillard and Longman note that "In 131 of the 167 times the verb 'give' occurs in the book, the subject of the action is YHWH."[31]

Law

After the review of Israel's history in chapters 1 to 4, there is a restatement of the Decalogue in chapter 5. This arrangement of material highlights God's sovereign relationship with Israel prior to the giving of establishment of the Law.[32] The Decalogue in turn then provides the foundational principles for the subsequent, more detailed laws. Some scholars go so far as to see a correlation between each of the laws of the Decalogue and each of the more detailed 'case-law' of the rest of the book.[33] This foundational aspect of the Decalogue is also demonstrated by the emphasis to actively remember the law of God (Deuteronomy 6:4-9), immediately after the Decalogue. The Law as it is broadly presented across Deuteronomy defines Israel both as a community and defines their relationship with YHWH. There is throughout the law a sense of justice. For example the demand for multiple witness (Deuteronomy 17:6-7), cities of refuge (19:1-10) or the provision of judges (17:8-13). The Law also features an important distinction between clean and unclean foods.

| Classes | Clean | Unclean |

| Mammals | Two qualifications: 1. Cloven hoofs 2. Chewing of the cud | Carnivores and those not meeting both "clean" qualifications |

| Birds | Those not specifically listed as forbidden | Birds of prey or scavengers |

| Reptiles | None | All |

| Water Animals | Two qualifications: 1. Fins 2. Scales | Those not meeting both "clean" qualifications |

| Insects | none | All |

Through history there have been several explanations for the rationale of this division. John Calvin asserted the division was arbitrary. Another suggestion is that some of the animals deemed unclean were used in pagan sacrifices. Other commentators suggest hygiene as a rationale. Finally some scholars suggest the rationale is symbolic and the cleanness of animals is based on their proximity to humanity.[34]

Obedience

Millar writing in the Dictionary of Biblical Theology sees the major theme of Deuteronomy as obedience.[35] The historical overview of the first several chapters demonstrate Israel's disobedience but also God's gracious care. This is followed up after the Decalogue, with a long call to Israel to choose life over death and blessing over curse, in chapters 7 to 11.[36] Daniel Block notes that the assumption in Deuteronomy is that "obedience is not primarily a duty imposed by one party on another, but an expression of covenantal relationship."[37]

YHWH

The book of Deuteronomy presents only YHWH as the God of Israel and speaks against the worship of other gods. For example in chapter 17 Israel is warned against worshiping the gods of other nations. This focus on the exclusive worship of YHWH has led some scholars such as Wright to say "Deuteronomy is uncompromisingly, ruthlessly monotheistic."[38] The focus of most of the book is YHWH. Throughout Deuteronomy either his actions, attributes or purposes are in view.[39] To the exclusion, notes McConville, of other deities.[40]

Worship

The centralization of worship is an important and repeated theme in Deuteronomy.[41] Dillard and Longman remark that the emphasis on centralization is designed to focus the hearers attention on the unique and exclusive holiness of YHWH.[41]

Deuteronomy in later tradition

Judaism: the shema (שמע)

Deuteronomy 6:4-5: "Hear (shema), O Israel, the Lord (YHWH) is our God, the Lord (YHWH) alone!" has become the basic credo of Judaism, and its twice-daily recitation is a mitzvah (religious commandment). The shema goes on: "Thou shalt love the Lord thy God with all thy heart and all thy soul and all thy might;" it has therefore also become identified with the central Jewish concept of the love of God, and the rewards that come with this.

Christianity

The earliest Christian authors interpreted the prophetic elements of the book of Deuteronomy dealing with the eschatological restoration of Israel as having been fulfilled in Jesus Christ and the establishment of the Christian church, composed of both Jews and Gentiles (Luke 1-2, Acts 2-5). Jesus himself was the "one (i.e., prophet) like me" predicted by Moses in Deuteronomy 18:15 (Acts 3:22-23), and St. Paul, drawing on Deuteronomy 30:11-14, explains that the keeping of Torah, which constituted Israel's righteousness under the Mosaic covenant, is redefined around faith in Jesus and the gospel (the New Covenant):[42]

For Moses describeth the righteousness which is of the law, that the man which doeth those things (i.e., who follows the Jewish laws described in the torah) shall live by them, but the righteousness which is of faith speaketh on this wise, Say not in thine heart, Who shall ascend into heaven? (that is, to bring Christ down from above) Or, Who shall descend into the deep? (that is, to bring up Christ again from the dead,) but what saith it? The word is nigh thee, even in thy mouth, and in thy heart: that is, the word of faith, which we preach; that if thou shalt confess with thy mouth the Lord Jesus, and shalt believe in thine heart that God hath raised him from the dead, thou shalt be saved.

– Romans 10:6-9 KJV

See also

| Books of the Torah |

|---|

- Biblical criticism

- Documentary hypothesis

- Mosaic authorship

- Deuteronomic Code

- Tanakh

- Weekly Torah portions in Deuteronomy: Devarim, Va'etchanan, Eikev, Re'eh, Shoftim, Ki Teitzei, Ki Tavo, Nitzavim, Vayelech, Haazinu, V'Zot HaBerachah.

References

- ↑ Ronald F. Youngblood, F. F. Bruce, R. K. Harrison and Thomas Nelson Publishers, Nelson's New Illustrated Bible Dictionary, Rev. Ed. of: Nelson's Illustrated Bible Dictionary.; Includes Index. (Nashville: T. Nelson, 1995).

- ↑ Christopher Wright, Deuteronomy NIBC (Peabody, Massachusetts: Hendrickson, 1996): 6.

- ↑ morfix online dictionary; in modern Hebrew this meaning is "smichut" (genitive noun construct), e.g. "לפי דבריך" = "according to what you said".

- ↑ L. Wilson, 'Pentateuch' Unpublished Lecture given at Ridley College. (May 2009).

- ↑ P. C. Craigie, The Book of Deuteronomy NICOT (London: Erdmans, 1976).

- ↑ W. Brueggemann, Deuteronomy AOTC (New York: Abingdon, 2001).

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Wilson, 'Pentateuch'.

- ↑ Craigie, The Book of Deuteronomy.

- ↑ Deut. 22:13-21

- ↑ Deut. 21:10-14

- ↑ Deut. 22:5

- ↑ Deut. 23:10-14

- ↑ Thompson, Deuteronomy, 48.

- ↑ Raymond B. Dillard and Tremper Longman, An Introduction to the Old Testament (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1994): 96.

- ↑ Wright, Deuteronomy, 7-8.

- ↑ Thompson, Deuteronomy, 52.

- ↑ Thompson, Deuteronomy, 54.

- ↑ Thompson, Deuteronomy, 56.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Dillard & Longman, An Introduction to the Old Testament, 93.

- ↑ Richard Elliott Friedman, Who Wrote the Bible? (New York: HarperCollins, 1997).

- ↑ Thompson, Deuteronomy, 58.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Dillard & Longman, An Introduction to the Old Testament, 96.

- ↑ J.G. McConville, 'Deuteronomy, Book of' Dictionary of the Old Testament Pentateuch (Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press, 2003): 183.

- ↑ Wright, Deuteronomy, 3.

- ↑ Ronald L. Troxel, Deuteronomy and the Torah Published Lecture delivered at the University of Wisconsin.

- ↑ J. A. Thompson , 'Deuteronomy' New Bible Dictionary (Leicester: Inter-Varsity Press, 1996): 274.

- ↑ Thompson , 'Deuteronomy, Book of', 274.

- ↑ J. G. Millar, 'Deuteronomy' Dictionary of Biblical Theology (Leicester: Inter-Varsity Press, 2000): 160.

- ↑ Norman K. Gottwald, review of Stephen L. Cook, The Social Roots of Biblical Yahwism, Society of Biblical Literature, 2004

- ↑ Dillard & Longman, An Introduction to the Old Testament, 102.

- ↑ Dillard & Longman An Introduction to the Old Testament, 104.

- ↑ Thompson, Deuteronomy, 112.

- ↑ G. Braulik, The Theology of Deuteronomy: Collected Essays of Georg Braulik (Dallas: D. & F. Scott Publishing, 1998).

- ↑ Gordan J. Wenham, 'The Theology of Unclean Food' Evangelical Quarterly 53 (1981) 6-15.

- ↑ Millar, 'Deuteronomy', 160-165.

- ↑ Millar, 'Deuteronomy', 161.

- ↑ Daniel I. Block, 'Deuteronomy' Dictionary for Theological Interpretation of the Bible (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2005): 172.

- ↑ Wright, Deuteronomy, 10.

- ↑ Block, 'Deuteronomy, Book of', 171.

- ↑ McConville, 'Deuteronomy, Book of', 190.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Dillard & Longman, An Introduction to the Old Testament, 104.

- ↑ J. G. McConville, "Deuteronomy", in Dictionary of the Old Testament: The Pentateuch (IVP, 2002); and "Deuteronomy 30:11-14 As a Prophecy of the New Covenant in Christ," Steven R. Coxhead, Westminster Theological Journal 68 (2006).

External links

- Book of Deuteronomy article (Jewish Encyclopedia)

- Teacher's Guide to Teaching Deuteronomy

- Deuteronomy by Rob Bradshaw

- "Deuteronomy 30:11-14 As a Prophecy of the New Covenant in Christ," Steven R. Coxhead, Westminster Theological Journal 68 (2006)

- "Deuteronomy 32:8 and the Sons of God", Michael S. Heiser, Bibliotheca Sacra 158 (January-March 2001)

Versions and translations

- Jewish translations:

- Deuteronomy at Mechon-Mamre (modified Jewish Publication Society translation)

- Deuteronomy (The Living Torah) Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan's translation and commentary at Ort.org

- Devarim - Deuteronomy (Judaica Press) translation [with Rashi's commentary] at Chabad.org

- דְּבָרִים Devarim - Deuteronomy (Hebrew - English at Mechon-Mamre.org)

- Christian translations:

- Online Bible at GospelHall.org (King James Version)

- Deuteronomy - Chapter Indexed (King James Version)

- oremus Bible Browser (New Revised Standard Version)

- oremus Bible Browser (Anglicized New Revised Standard Version)

- Deuteronomy at Wikisource (Authorized King James Version)

| Preceded by Numbers |

Hebrew Bible | Followed by Joshua |

| Christian Old Testament |